This is a great reference on Chinese tea background. It's by Sergey Shevelev, the founder of Moychay, probably the main Russian tea vendor, and developer of a series of tea clubs (not exactly like a cafe). Sergey talks about the book, about what went into it, and what it means to him, in this video gathering description (which seems more about talking through a tasting session, to be clear; I mention it more to bring up the video theme and location). There are more book details here.

Sergey has been a very positive and helpful tea contact for awhile, and I helped do a final read-through of this text, and Moychay sent some teas in thanks, so in a sense I'm not impartial. Maybe hardly anyone ever is completely objective about almost anything they experience, but that's leading into a different set of concerns. To me I seem to have no problems at all communicating exactly the same thing I would based on a different connection context, or a complete lack of one, but who knows. This post might go a bit far in the opposite direction, describing what I see as limitations in the work, which are more about scope choices and related to which interests it applies to, since I thought the content was quite good.

It's interesting comparing and contrasting this topic scope with another tea text I did a late-stage editing read through for, Tony Gebely's Tea: A User's Guide. It really helps place what this about, the range. Both are quite good texts, I think, both very informative, detailed, and well-grounded, but the scope covered is quite different. There some overlap related to some tea processing and types information, but in general that text is all about user experience of and approach to tea, and this is about deeper background context than most people would ever encounter.

This book is mostly about tea types, plant type inputs, locations, history, regional geography, processing steps, and so on, of course mostly limited to China, with some coverage of Taiwan, which may seem to overlap or be completely separate, depending on the subject being considered. For tea it overlaps. Since it mentions a lot of natural spaces, parks, and tea oriented landmarks in different places it overlaps with what a tourist in China focused on tea would seek out and experience. It's not as much about related legends, which do come up here and there, so some main ones are included, but there is more about that non-fiction background. It doesn't really cover brewing approaches, ceremonial aspects, or teaware either, at least some of which Sergey mentioned in that video cited as being covered in a separate text still under development.

|

Sergey making pu'er (he's the one on the right) |

It's funny how much there is left to cover, given that. It runs long because it doesn't stop at describing the best known areas and types, and ventures on to geographical descriptions and processing steps. The first 50 pages is about tea culture and historical background, with a bit on tea plant compounds (which does overlap with Tony's book), but the rest of the overlap with Tony's reference is really with a lengthy list but abbreviated depth description of tea types, with this going a lot further on what those are and how they are produced.

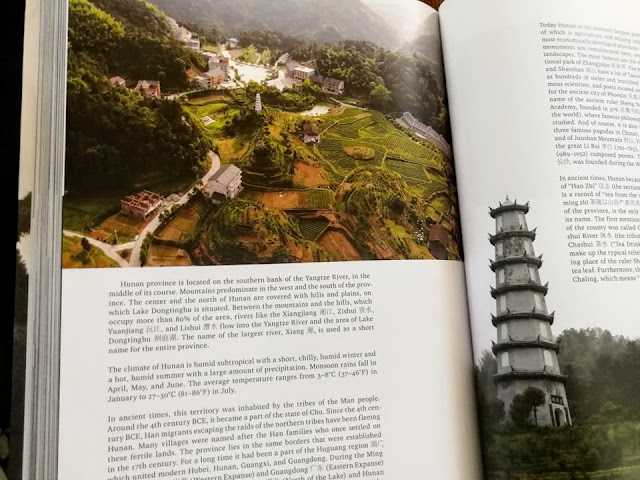

Pictures tell a lot of the story; clear and impactful images of the famous and not as famous tea growing areas really fill in a sense of those places. Then images of the actual teas and processing steps also round out a little on what a broad range would be like, venturing into tangents like aging background, as is relevant to the type being described. History of every area gets detailed treatment.

I suppose that means this book wouldn't be for everyone, going the extra couple of layers deeper beyond what tea experience itself is about. Tea processing is a fascinating subject to me, but even that only goes so far in informing the actual experience, and less so the history. For a range like oxidation level background it does apply to experience, because the text talks through what the most conventional styles are like, with less on what other variations and style interpretations might be like. I don't mean just for Tie Guan Yin, pu'er, or Dan Congs, I mean for a very broad range of popular teas from across China, some of which aren't very familiar in "the West."

|

even for the more familiar historical sub-themes the extra details are is still interesting |

In describing what works best about Sergey's communication about teas in the past I've always mentioned that he is a true tea enthusiast, in addition to being a vendor, with that other natural focus on the commercial side. No doubt the history and background was always fascinating to him too, and this book represents ideas collected over many years and visits to China (at least 10, he mentioned), ideas which were previously only brought up in narrow scope video content. He has long been a student of Chinese language, which might work as a general cut-off for how far someone tends to take dedication to the range of subjects.

On the opposite side, for people who are bad with languages, not going there and not studying Mandarin doesn't seem to represent a gap or lack of commitment. I was a lot more open to foreign language studies earlier in life myself, studying French, Spanish, and Sanskrit in academic circumstances, and now my Thai is still fairly limited even for living in Thailand for 14 years. I suppose that partly relates to the added difficulty of moving beyond Latin based languages; learning Devanagari--traditional Indian language script--to study Sanskrit came a cost to me, and pushing through different language forms and structure seemed a bit punishing, and didn't go well. Or maybe my brain is just less plastic now? Hard to say, but it seems to relate as much to motivation level.

One part of how this approaches describing teas stands out as what some would interpret as a strength of the work, and others a weakness. It describes type-typical experienced aspects in specific tea versions, or I suppose more accurately as one relatively typical version might be interpreted. That's great, for passing on a sense of what a type might be like. For people looking for gaps, with a negative bias, it could seem to introduce error, since any given type occurs as a broad range of exhibited aspects, with the "type-typical" theme only being so narrow.

I don't see it as problematic describing that. Any text would trip over itself trying to describe exceptions to every generality or a more complete flavors / taste / aroma range, and typically skipping that makes the most sense, to me. One tea expert in particular comes to mind in mentioning that, an old favorite blog based reference who started discussions and an answer to every question with "it just depends," using half the answer content space to address context and range of exceptions. To me that approach works too, since the placement of ideas and discussion limitations are also interesting, but not to cover this much scope. It works better in a short passage to emphasize limitations, talking around and placing a narrower idea range, than to go through that over and over in a long text.

For the tea history, area descriptions, about type ranges, and general processing descriptions it's not as relevant anyway; it comes up more in discussion of aspects of types as a sensory experience. This work passes on a sense of a typical experience range, but doesn't try to replace experience, or account for exceptions. To cite an example of the kind of thing "left out," as a tea reviewer it's interesting to try to identify what I see as "quality markers," what sets apart the best versions of types, but really I think it's best to not venture into that subjective a scope in a broad work like this. The other text on tea I mentioned, Tony Gebely's work, made the same scope decision to focus on general types descriptions, and not get swept into what separates quality levels, which again I think is for the best.

As I keep encountering more and more detailed tea background, and talking to vendors about processing themes and such, it's harder to find new ground I've not covered. Half of this text was relatively unfamiliar, because I'm not an expert on how to process teas, and I've encountered a lot more about main tea areas than others (eg. Wuyishan and Yunnan, versus entire broad regions that I wasn't really clear on covered in great detail in this).

One might wonder, if a lot of Chinese people really do drink ordinary quality and relatively "generic" tea (an idea that comes up, which matches my experience), how is it possible that there is so much detailed background available on such a broad range of areas and types? This seems to be a look into what informed locals would know and experience about their own area, types, and history, or that degree of coverage plus a bit more. We are already exposed to some of that in those places I mentioned, Wuyishan (a Fujian area) and Yunnan (a whole province), but Chinese tea history doesn't end at those sorts of better known areas. I don't just mean related to hei cha and a few more types of green and black tea either, and yellow tea; there is a broader and deeper still-living culture and history to be explored.

One might wonder if it wouldn't feel incomplete, like a gap, to hear about another dozen or more types of teas--or maybe 50, or more--and to not experience them, to only encounter them as ideas and description. Sure, I suppose it could. Also this treatment may not be as interesting for people who tend to narrow in on one range of teas they like and leave the rest aside the broad background exploration theme. There's nothing wrong with only drinking oolongs, or sheng pu'er. This book is mainly for people who like the background of tea in addition to the experience of it, although it could be used differently, for example as a narrower reference for specific types, or as an intro to the theme of tea processing.

For being a relatively long book, 511 pages, this isn't a difficult read though. Again pictures tell a lot of the story, so actual text is much more limited, and it being separated out by broad and then narrower geographical areas make it approachable and much easier to read.

For people into texts as a reference in general, and to the scope I've outlined in particular, I would definitely recommend this book. As with most people I tend to consume more content related to shorter online videos myself, but there are different strengths and limitations related to the two forms. It would take many hours out of a year to get to this much detailed content online, and one never would run across all of these same ideas, across any exploration time frame, not even a decade.

On the Chinese language internet that may be more practical, but English Western web text or video sources just aren't that readily available, detailed, or complete. Sergey's Youtube videos are a nice exception, or Farmerleaf's, and TeaDB is a good video blog, and the Tea House Ghost channel a nice reference, but all of these only treat one narrow and typically more conventional topic in short videos, with substantial focus on practical advice and perspective. They just can't explore the tea history, geographical input, processing, and types descriptions from many main regions in China in the same way this text does.

No comments:

Post a Comment