|

in the Tea Village shop tasting area (in October) |

When I last visited the Tea Village shop in Pattaya one owner, Vee, let me try a really interesting version of aged pu'er that seemed as much like a hei cha. That's essentially what this is. I'll let his website description of it tell more of the details:

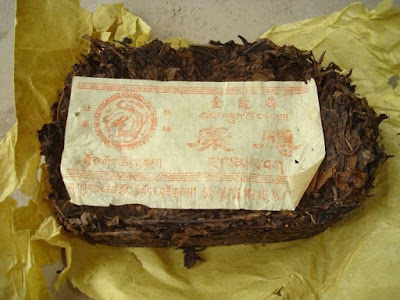

And that's what it is; just a bit of a mystery tea. The "made in the Tibetan style" more or less says "hei cha" to me, and tasting it does too. It's a fine material, very hard pressed tea, which was very difficult to extract for a brewing sample. Vee used a hammer and chisel to remove this part, I think it was, and I used a pick for pu'er, a knife, and eventually a bottle opener (it gave good leverage and mechanics for snapping off small chunks).

You read that one part right; they sell this as 2 kilogram bricks, equivalent to nearly a half dozen typical size pu'er cakes (although it lost weight in storage, so it's down to only 5). It sells for 12,900 baht, now equivalent to $393. For five tea cakes worth of tea that comes out to around $80 a cake, a pretty good value for 21 year old tea. Of course it's not pu'er, so it needs to be compared to a hei cha scale instead (in my opinion), and I doubt there is enough equivalent product on the market for this for there to be any clear fair market value. If you want it you have to find it first, which is essentially all but impossible, and a vendor can charge whatever they want for it that makes it sell.

As for what the tea tastes like I've had it before, in the shop with him, and it seems like a hei cha to me. It's smooth, rich, warm in effect, and centered on the plum-like range that I've encountered in other hei cha. "Plum" may or may not be the best description for a primary taste aspect but it gets across the general range. Onto tasting notes then.

|

looking bored with the tea theme right away |

|

I think this was that tea, from trying it there |

Review

The story of this tea starts with how hard it was to break up. That initial chunk Vee used a hammer and chisel to break off, I think. I tried to use sharp spiked tea pick to flake off some pieces but that didn't really work. Eventually I used that, along with an actual knife (luckily that didn't end in me impaling myself), and finally a bottle opener to crack off some pieces. It's a well-compressed tea.

I used a standard brief rinse for this tea, which wasn't going to do much for getting the small chunks of tea started brewing. It was a judgement call as to how to brew it, related to what I broke off including both dust and small chunks. It's not optimum to brew two completely different types of material together, since that dust will be starting to infuse within a second round (the first after a rinse), and the chunks will take a few rounds to even get soaked enough to start. When I drank the tea with Vee we had at least 10 rounds of it and that tea may well have continued for that much longer. The issue I'm referring to is uneven infusion exposure instead of longevity; one part of the tea will be brewed out (changing flavor to where teas that you discard as spent are in the cycle, often turning woody in flavor character) while the other just starts going.

The obvious work-around is to separate out the finer material and not use it, to set it aside for a later round. I didn't do that though. Per my best guess this tea won't "brew-out" to be unpleasant, but instead will retain a similar character and just fade over a very long infusion cycle, so it won't make as much difference. And as usual intuition is my main guide for how to approach brewing teas; somehow my gut said the right thing is to mix it all and use it together. Of course it's hard to track how frequently that's wrong.

|

a bit too light |

I brewed the tea for around 10 to 15 seconds for a first infusion, which turned out to be more of a second rinse, too thin to get a lot of effect from. Then for 30 seconds a second cycle, to get the tea chunks started soaking and to get the dust pretty far along, and mixed those two infusions ("stacked" them, to use the catchier formal term). From here on a more standard approach should work, something like 15 second brewing times. I just checked Vee's website recommendation and they said to use two rinses; that makes sense. From there adjusting time as works best for you is the way to go.

This first infusion won't be the best representation of the tea's character but it's nice. It has that plum effect already. Mineral is present as a base but it's in a really soft and subdued form compared to the sheng and shou themes I've been on. It's the other layers of complex flavors that make this nice, which are harder to pull apart. One part is like incense spices, frankincense or myrrh (I still have to get my incense habit going to tell what that is though). Another is a very fine trace of menthol.

As a primary flavor aspect I hate menthol (just a personal preference issue), so that #18 Ruby or Red Jade black teas from Taiwan almost always seem awful to me. As a minor supporting element that integrates will with the rest is a completely different case; that can be great, and this works. From there I could keep going but it seems as well to add more description related to a second round instead.

Second infusion

This opened up faster than I thought it would. It seems to be loosened up and brewing nicely already. I gave it about a 15 second infusion time, about twice as long as it would need to draw out flavor if astringency or other aspect moderation was an issue but this tea will be nicer at a slightly more intense brew intensity. That's just a matter of preference; it would work well brewed wispy light or twice as strong again.

The same flavor list as last time applies: plum, mineral, some supporting spice (which is continuous with some dark wood tones), and just a hint of menthol, which might be more faint, so that I wouldn't identify it in this round if I hadn't noticed it in the last. It's nice the way that complex mix coats your mouth and remains as an aftertaste effect. There isn't that much structure to the mouth-feel to talk about; the intense flavors give it a complex over-all effect but not a lot of mouth-feel structure supports or contributes to that. The wood is similar to redwood, that aromatic, almost spicy range of wood tone.

The mineral is more intense in this round; it really covers such a range that it would be possible to write a short review description of just the mineral. It's warm and complex in nature, towards that artesian well / red sandstone range. It extends to being almost metallic, which could be a bad thing depending on the metal character, but it works in this. It's not completely different than rusted iron bar but it seems to extend to metal-range complexity. For being a flavor-intensive but simple in structure tea experience this covers a lot of ground.

Third infusion

|

mostly wetted and loosed up already |

It's not transitioning; the taste is like before. I could keep free-associating to come up with different interpretations for the same set of flavors and other aspects. Probably the balance of what is there has shifted a little too; there's more that could be said about that. That menthol background element is so faint that it may or may not be there at all at this point, but I'm going to say that it is.

|

dried persimmons! I'm not sure what this coated version is covered with. |

Which reminds me, I was just in Chinatown and walked by those, and the looked really nice, but I was in a hurry and didn't buy any. I love those; that flavor is as close as anything else to fig (so this tea isn't far from that either), but it's just a little lighter (but just as sweet), less rich but more complex in some sense that's hard to place.

Fourth infusion

I'm running out of time, off to get a haircut after completely losing any style due to not making that work. It's still similar. I remember that from trying an awful lot of rounds with Vee; it stays fairly consistent. I like this character so that's a good thing. I think the mineral and metal levels move around a little, that the relative proportion of those individual aspects is varying, but the overall character and effect aren't. The aromatic wood component seems a bit stronger this round.

It's my impression that changing infusion strength shifts that balance a good bit for this type of tea. It narrows things down that astringency and mouthfeel in general isn't a concern; optimum is whatever seems best for taste. Aftertaste is substantial too, but it still occurs in a lighter brewed version. Probably shifting temperature would change things a little too but I can't imagine that using anything other than full boiling point water makes any sense (not that I'll check that).

It's a very nice tea experience. I've had a hei cha before that this reminds me of, a version of Fu brick. It's a bit simple in effect; you either like that flavor or you don't. The flavor is complex, and it wouldn't be familiar to everyone, but to me it's likable. I'm not going on about how clean it is but it helps a lot that there is no trace of mustiness in this tea, or that the metal, fruit, and earthy range balances as well as it does.

This tea is probably far from finished; there might be another 15 infusions to enjoy out of it. It'll be nice if it works out that I can do another full session in the afternoon with it since I'll squeeze in a couple of more and be off for now.

Fifth infusion

|

completely loosened up |

The balance of those aspects is definitely shifting around. It's much stronger towards the redwood / aromatic spice range now, although there is plenty of dried persimmon flavor balancing that (and related sweetness), and a nice dryness from some very complex mineral. That probably works well as an overall description of this tea, even though earlier the aromatic wood was lighter.

Later infusions

I drank a couple more infusions before going out, and left the tea fully drained to try again the next morning (early afternoon; I got a late start on it). Using extended infusion times to keep the intensity up changed the character in an interesting way, drawing out more earthy leather range flavor, still with good molasses sweetness, and a bit of spice, again supported by mineral tone. The molasses and leather trailed into a tree-bark edge, but it was still nothing like astringency in other tea types.

Placing that style; potentially related tea versions

This tea is a little different than anything that I've tried, but all the same I'd like to cover a little more about the teas closest to it in style that I've tried. I mentioned a Yunnan Sourcing Chinese hei cha that was similar, which was their 2007 Xiang Yi "Hei Cha Zhuan" Hunan brick tea, which I reviewed here.

To be fair to this Tea Village version it probably a was a bit more refined and distinctive, beyond just not being the same thing, maybe because the extra decade of aging helped it, or maybe it started out different. It definitely doesn't look similar, even though the brewed character shows some similarities. This tea just reviewed is made of fine material, very tightly pressed, with that other hei cha more from larger leaf pieces, along with a good bit of stem.

|

the initial chunks of that tea, YS Hunan brick |

|

broken up in a gaiwan |

|

loosely compressed compared to this other tea (credit YS site) |

Even though they're probably not the same the character was similar, so I wanted to add a bit more about what it was, from that YS vendor description, which I'll explore further with other types descriptions afterwards. Part of the point is to try to zero in on what that tea was in more general terms; for example, would it have been pre-fermented or not (as it was described by Vee).

Back to that Yunnan Sourcing Hunan brick description:

This is from the Xiang Yi Tea Factory in An Hua county of Hunan Province. Xiang Yi is the second oldest producer of Hunan Hei Cha after Bai Sha Xi Tea Factory.

Hei Cha Zhuan (lit. Black Tea Brick) is composed of An Hua grown tea that's been picked and processed with frying, rolling, wilting and then sun-dried. The bricks are tightly compressed which allows for slow but determined post fermentation. These are unique from Fu Bricks in that the golden flower spores are not introduced into the tea and as such don't exist.

This particular brick was stored in An Hua County of Hunan from 2007 until June 2016. The smell of the dry leaf is that of dried fruit... very sweet and dense fruitiness happening. The brewed tea is sweet and thick with (not surprisingly) strong fruit sweetness (think dried plums). Tea can be infused 7 to 10 times if brewed gong fu style. We recommend loosening the tea using a pick into smallish chunks layer by layer. We also recommend using a clay pot and the hottest water possible.

One of things that stands out about this tea, besides the unique character, is the unusual level of value; they sell it for $126 for a one kilogram brick. Supply, demand, and production costs all factor into a final tea price and apparently this end up being inexpensive. Description in my review summarized flavor aspects as:

"fig, older hay bale, mineral, and molasses as a start but really I think cocoa sort of works, and there's another dried fruit element that's quite pronounced..."

I think that may have been a bit mustier, and also complex but maybe not in exactly the same way. It's interesting that this tea version isn't post-fermented through any piling step, isn't it? At least as presented, but the description from original content could be clearer. I lose track of what typically is or is not though. I'll cite a reference about this type (the YS version; not this Tea Village tea, since it's not as clear what it even is), from Tony Gebely's Tea: A Users Guide (a really good general reference for a lot of scope):

Hei Mao Cha (黑猫茶, hēi māo chá), Semi-Finished Dark Tea

Nearly all styles of Hunan hei cha begin with the production of Hei Mao Cha or semi-finished dark tea. Hei Mao Cha is made by fixing, rolling, pile-fermenting and drying fresh tea leaves, usually from descendants of Camellia sinensis var. assamica known as Da Ye Zhong (大叶种) or large leaf type. Another way to refer to Hei Mao Cha is pile-fermented Mao Cha.

Note that this says "nearly all styles," and goes onto say this generally refers to a pile-fermented tea. Of course the Tea Village product description cites that being made based on a Tibetan tea type instead, not Hunan (China), but versions of that aren't listed in this book reference. The description of it as "sheng" (which means "raw") refers to it as a non-pre-fermented tea, although I'm not sure if that's intended as a conclusive description or not.

That description cited was only about the general category; a further passage from that User's Guide reference relates to this YS tea type I'd mentioned:

Hei Zhuan Cha (黑砖茶, hēi zhuān chá), Dark Brick or Black Brick Tea

Hei Zhuan Cha is a fermented tea made by steaming Hei Mao Cha and pressing it into special rectangular molds. The bricks are then dried in a warm room and wrapped. The finished product is a rectangular brick with a flat surface, usually without markings.

It doesn't fill in much, and that's especially not helpful for not clearly linking back to the tea type I'm reviewing anyway.

Tony's book does list another type from China most typically used to make Tibetan style yak-butter tea (the association to that country that does come to mind), describing that hei cha as follows:

Kang Zhuan is a style of Nan Lu Bian Hei Cha brick from Sichuan province. Kang Zhuan is made up of a mixture of older tea leaves and stems... Leaves and stems destined for Kang Zhuan are fixed, rolled, and pile-fermented... Kang Zhuan tea is the tea of choice when making Tibetan Yak Butter Tea. Production of this tea has spread from Sichuan to Hunan and Guizhou.

Not onto Tibetan originated tea yet (given there is such a thing; I think there is), but that does mention that final preparation style from there. That sounds a lot like a tea I tried from Moychay, an odd looking pressed large brick made from a good bit of stem material and leaves, reviewed here, and pictured as follows:

They made no type or style claims in selling that tea, and even made it clear that it wasn't like other standard types of hei cha. That review actually covers one of my favorite sheng from them, in the first section, a really nice, fruity version from Nan Nuo. As far as that tea goes it was a bit rustic; as I remember it tasted a bit like barn door.

Yunnan Sourcing does list a version of that last tea type (mentioned in the Tea: a User's Guide citation), with the description connecting with that reference:

These "Kang" bricks were produced in the small tea factory in Province of Guizhou and then sent to Tibet where they were stored in a family home for more than ten years. These are packaged in long (1 meter) bamboo baskets, about 20 to each length.

|

credit related Yunnan Sourcing page, the link just cited with the text |

Given this tea I reviewed seems to contain no stem material at all (unless that was ground too fine to identify), was finely ground leaves, and was well-compressed into a brick shape instead it doesn't seem to be at all related. Even if I did research for other different Tibetan style compressed tea versions (a reasonable next step) it would be hard placing those in relation to this tea without tasting them, or probably still difficult even with trying them. It would be easy to note how close aspects land but not possible to separate out different causes for why (eg. tea plant type differences, growing area as an input, processing differences, where the teas spent the last 20+ years).

At any rate this was an interesting and unique tea; it's always nice trying those. With more research it would probably be possible to come to a better guess about what this is. Enjoying it for what it is in the cup doesn't require all that; the tea was nice.

Later edit: I spoke with a reference about what it is, with a person who would be familiar with it. That person said it's not uncommon for fannings (ground up tea by-product) to be pressed into bricks in Yunnan, and that those products are usually sold for next to nothing. Here is an example of one; a 6 kilogram brick that's selling on Taobao for around $29, or a 3 kg version selling for about a third of that.

Of course quality level and material used is going to vary, and how any teas taste.

Related to the "Tibetan" background and age claims according to that reference this probably has nothing to do with Tibet, and the label doesn't look conventional for being 20 years old. And the tea itself claims to be from from 1962, pressed onto the surface lettering: 一九六二制 literallly means "Made in 1962." It's not relatively new raw tea material but it's absolutely not 50+ year old tea, and the claim that it's 21 years old also seems dubious based on this latest input.

I tend to not express views or background about products that is negative here, and I respect and personally like this vendor. But at a guess this tea is just an inexpensive, relatively recent production made to be sold to tourists. I doubt Vee knew that, and there's a good chance that he still doesn't. There's even some chance that's wrong, but I'm completely convinced this reference source is as good as any person one could talk to. I won't cite who that is explicitly, since there is a convention in tea circles to initiate a dramatic cycle of blame related to anyone making any negative claims at all.

This same theme repeats over and over related to online tea sources and local Bangkok Chinatown vendors; you really should expect the story and label content for pu'er to potentially be completely false unless you have clear reason to believe it, and not the other way around. If you can try a tea first and buy it based on experienced aspects versus a story being told or value claim that's even better.

Hi,

ReplyDeleteI had a look at the vendors site. He lists a Dayi 7542 (batch 809) for US$ 215. You've got to be joking! Based on the gross overpricing of this cake I would guess that this 2kg brick is similarly overpriced. You can get an idea of prices for this kind of tea from Chawangshop

I've amended this post to mention a pu'er and hei cha expert's input since I've checked comments and unfortunately you're almost certainly right; this tea is probably radically overpriced. Without background I couldn't really speculate on that initially but including mention of the closest related hei cha had allowed people to look around and come to their own conclusions. I'm not sure to what extent this is a case of a vendor taking advantage of people versus just not knowing the background of a tea range. I don't know what he paid, and it seemed he just didn't know what range it was in. It's odd given that the standard products he sells had always been in a relatively low price range, really where they should be for Thai oolong and such. They've bumped up some but what I've tried of other teas seems reasonable; they're moderate quality, moderate cost. It's just not the place to buy pu'er.

Delete