I was talking to an online friend recently who asked for input about meditation. I'm not exactly an expert, probably closer to the opposite, just someone who dabbles a bit, but I have been meditating quite a bit lately, averaging more than half an hour a day for 2 1/2 months.

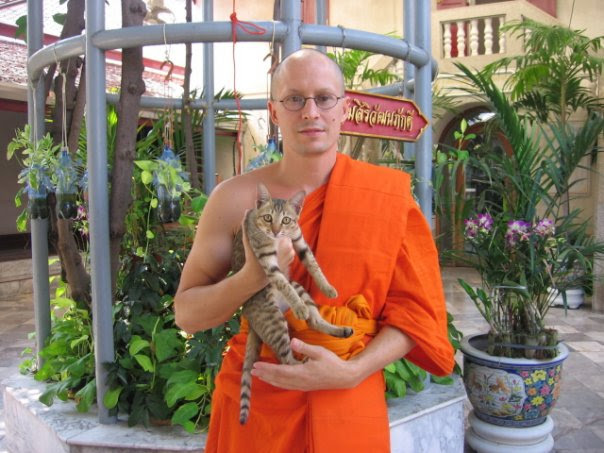

I was ordained as a Thai Buddhist monk 16 years ago, and I received formal training in meditation in a center at that time (daily training sounds strong; I visited the center, at least, but their input was limited). I was only a monk for a bit over 2 months, which might sound short, but it's nearly two months longer than the standard stay of two weeks for a younger Thai man to temporarily ordain. That part is complicated; let's get back to the meditation theme, leaving out my background about a couple of other short term trial periods, the first of which was way back when.

That discussion and input covered what seated meditation is about, not intended as comprehensive background or complete practical advice. I'll add some thoughts afterward, but never will cover either in lots of detail. This is basically that input word for word, not adjusted much:

Of course it's complicated, and people would say different things, and I'm not really some sort of expert.

Your experience would change over time, and probably your approach with it. Initial expectations could also vary, with people seeking different goals.

Probably it's best to set aside what benefits might occur, even though intention and perspective are the main starting points. Let's say that you want to experiment, and maybe increase mental clarity, patience, and a limited degree of insight into your own nature, and that of experienced reality. That works.

A main initial factor will be your tolerance for sitting, how it feels physically. If you plan to sit for only 10 minutes I think that won't be an issue, but within 15 to 20 it probably would be. Maybe adjusting by starting out with short sessions is good, so you don't have to work through too much related to that part. We all carry tension in our bodies much more than we realize and use constant movement to work through it, on a subconscious level. Being still triggers a negative response of tensing up more. For 10 minutes it should still be fine though.

Mentally, internally, there are different types of practices. I've trained some and the range of what I've heard and experienced doesn't narrow down well, but I'll narrow it anyway.

The idea is to still your mind, to an extent. It won't work to take up internal quietude, so next it turns to how to approach that, not to resolve the noise but to work through it. Watching your breath is a common technique, or focusing attention at some point in your body, often the stomach at or around your navel. To focus on breathing you can focus on a point where it moves, in and out of the tip of your nose, or for me focusing on relaxing and breathing from your diaphragm works better.

If your mind is a real mess of noise counting can help with that. As it settles some turning to focus attention on breathing at your stomach can work better. The mental practice is about how to deal with random thoughts, or daydreams. Common advice is to acknowledge thoughts and let them go, to not keep following them. That sounds more like stifling thought than it ends up relating to. You can't force your mind to stop thinking. You can gradually let it settle over time. In 10 minutes, even practicing for days on end, you might not seem to experience mental quietude, but it can settle some.

There is potential usefulness in the noise. You already know which lines of thought you continually return to, what your concerns are, but you might be avoiding directly experiencing these, and accepting them can be helpful. It's possible that insight could occur, a part that you haven't considered, but at first you experience noise, then acceptance of the issues can help quiet that some, then a more calm but still random thoughts based inner experience can seem different. It's at this point that a different form of progression begins. On the other side of that limited experience of mental stillness is possible.

One might wonder what the point of putting hours of effort into not thinking anything might be. It's about calming your mind, not just temporarily stopping it. That calm can and will extend to greater calm all the rest of the day. It's not magic, it only goes so far, but mental clarity and stability are hard to pursue in any ways. Exercise can help a little, and I think the two experience forms overlap more than people might expect. You take focus off your body by sitting motionless, but running for an equivalent amount of time also frees up space for internal focus, even though keeping yourself moving also uses some attention.

I've experienced stress--physical tension--moving from one place to another within my body as I've meditated over the past 2 months. I can't really place that as meaning something in particular, I'm just including it for completeness. I've experienced less mental or emotional change than I would have expected. Some, but not so much. Maybe I feel slightly more stable and grounded, even though I've been through a lot in the last 2 months.

|

a bit off topic, Keo ordained as a novice once too (covered here) |

Background context reference

There's a lot that I could add, about what my life context has been like recently, or what doesn't seem clear and developed in this.

First I wanted to mention a background context reference. A friend recently recommended this site for a lead on where to practice, as a meditation center (a large set of those, I think), promoting 10 day retreat practice, the Goenka organization (maybe not used as an organization title reference?), linked at dhamma.org. It talks about background and covers limited information about practice, but of course most of the "how to" part is only conducted on retreats in person. Let's sample a bit of context though.

To be clear what I was taught was described as vipassana, the form of meditation they describe. It's hard to say if the two forms are quite similar or not; maybe the category name is the same but actual practice differs. Their description:

Vipassana, which means to see things as they really are, is one of India's most ancient techniques of meditation. It was rediscovered by Gotama Buddha more than 2500 years ago and was taught by him as a universal remedy for universal ills, i.e., an Art Of Living. This non-sectarian technique aims for the total eradication of mental impurities and the resultant highest happiness of full liberation.

Vipassana is a way of self-transformation through self-observation. It focuses on the deep interconnection between mind and body, which can be experienced directly by disciplined attention to the physical sensations that form the life of the body, and that continuously interconnect and condition the life of the mind. It is this observation-based, self-exploratory journey to the common root of mind and body that dissolves mental impurity, resulting in a balanced mind full of love and compassion.

So far so good, but it doesn't say much about the purpose, in detail, or the actual practice. This part goes further:

Therefore, a code of morality is the essential first step of the practice...

The next step is to develop some mastery over this wild mind by training it to remain fixed on a single object, the breath. One tries to keep one's attention on the respiration for as long as possible. This is not a breathing exercise; one does not regulate the breath. Instead, one observes natural respiration as it is, as it comes in, as it goes out. In this way one further calms the mind so that it is no longer overpowered by intense negativities. At the same time, one is concentrating the mind, making it sharp and penetrating, capable of the work of insight.

These first two steps, living a moral life, and controlling the mind, are very necessary and beneficial in themselves, but they will lead to suppression of negativities unless one takes the third step: purifying the mind of defilements by developing insight into one's own nature. This is Vipassana: experiencing one's own reality by the systematic and dispassionate observation within oneself of the ever-changing mind-matter phenomenon manifesting itself as sensations. This is the culmination of the teaching of the Buddha: self-purification by self-observation...

More detailed, and of course that's as far as web page content is going to go. Again I'm no expert, as I suppose the people guiding others in a meditation center probably would be, but I'll still get back to adding some clarification to that advice to a friend.

Another book reference, Mindfulness with Breathing, is good for outlining in very practical terms how our body and mind are linked by breathing patterns and mental state. I'd recommend that even for people who have no interest in meditation; it's interesting, and fairly easy to notice and confirm--the initial parts--just by observing your own mental states and breathing forms.

The basics are this: when we are very calm our breathing is naturally very smooth, deep, slow, and even, based from our stomach / diaphragm, and when we are mentally agitated it is based from our upper chest, is shallower, faster, and the airflow is more constricted. It mainly works the one way, with breathing reacting to mental state, but you can even turn that around, and breath slower and deeper to calm your mind. Or to an extent you can breath faster, shallower, rougher, and higher in the chest to trigger a more agitated mental state (not that a need for that would come up so often, but it's interesting to try out).

Further discussion

I had never really did much with developing why one might meditate in that, although on a fast read it might seem as if I did, since I added a conventional possible set of goals within that. That was there more as a place-holder than a likely list of potential benefits; one would probably meditate largely to experience the effects for themselves, with only vague expectations about potential benefits. Or maybe within the context of other learning the goals could be quite clear and detailed, even including stages of expectations and varying levels of goals. Maybe it would be just to remain more calm, be more focused, or control temper; there's no reason why goals would need to be elaborate or exotic.

It could include a spiritual / religious context, or mental-state goals and expectations could vary broadly, so that the question "why meditate?" is too much to cover adequately. Let's set that aside again.

I didn't add much about what I've experienced, even though I've mentioned that I just meditated for over two months (almost 3 now), about the same time period I was ordained way back when, so I've been meditating for longer now than then. There isn't much to say, really. I feel slightly calmer and more stable, but I felt somewhat calm and stable before. The way my body experiences retained tension has changed, but of course that was never an initial goal, and I'm not sure that it's helpful.

In that website, for that meditation center, they describe how meditating for 10 days, many hours a day, is often experienced as transformative. I've not experienced that. Probably my own less informed practice wouldn't lead to that, even if I could somehow work up to comparable exposure, two work-weeks worth of practice time within a week and a half.

So shouldn't readers disregard this, and listen to a Goenka-trained practitioner instead? Sure; you should probably do that. I'm passing on discussion with a friend, based on limited exposure myself, and it's uncommon to hear from a friend in such a way, but if you can tolerate some reading in a limited sense you will have done so (someone acting in that role, at least).

I tend to do that, discussing subjects I'm not an expert in. I talk about fasting here, even though I've only fasted for about 25 days over the past year (water fasting, essentially, but I've also been drinking tea). I mention experiences with running, and I'm not much of a runner, having built up to training for 20 miles or so a week this year, falling well off that for months now (first due to Bangkok heat, lately related to minor knee problems). I don't even run races, although I have in the past. 10 years ago I started writing about tea here, and I'd only had limited exposure to the subject back then, only trying a couple of dozen versions of loose tea by then. It's awkward looking back on those early posts.

Back to closing thoughts, what I've left out earlier. It's a little odd moving so directly past why to meditate, what better goals might be, or later expectations, but given the context I'll have to. I can say a little about what limited exposure has been like, I guess nearly 40 hours of trial over more than two months.

I might have understated what that body tension experience is like. Meditating for 15 to 20 minutes might still be ok, but the tension in your body tends to collect in places and express itself more than one might imagine. I'm sure that must vary a lot by individual. For whatever reasons for me I feel fine for the first half an hour or so, and then tension issues become a problem. The effects vary day to day. Some days it's not really an issue, and some days I quit after half an hour because one leg is asleep or cramped.

In that temple training center I was discussing practice with guests and a young woman, who was a regular there, described the issue of discomfort while sitting, which stuck with me. She said that she tries to make the pain experience seem smaller in her mind. In a way that seemed to work, and it also missed part of how I saw it. It had seemed to me that fully accepting the physical feeling helped you move through it, and any limited form of mentally rejecting it or setting it aside would make it worse, because it was going to remain a big part of your momentary experience. Not wanting to feel it was worse than the actual feeling itself, in the same sense that it can be maddening to wish the planned time ended, because you absolutely can't affect the rate of flow of time. Moving on...

The experience of patience is interesting, seeing the experience as unpleasant versus neutral or positive. That fades as it becomes normal, over a relatively short time-frame, within a couple of weeks or so, but earlier on very trivial discomfort brings up an aversion to continuing. That must vary by individual? It seems normal before long, not positive or negative, although as physical discomfort increases that can shift. For the rest it will go without saying "that must vary by individual," just assuming that the context here is talking mostly about what I've experienced over the last three months, and less so related to the other two times I meditated regularly.

The experience of flow of time changes, a lot.

One might wonder about inner voice issues; to what extent would your mind become quiet, or not? It does quiet down. Early on it seems noisy as could be, then daydreaming and tangents replace that, and only then it begins to still. I don't know that there's any sort of more positive condition associated with more quietude; it's interesting, but the experience seems to be about calming, not becoming calm. The noises tell a story, or different stories. For me the daydreaming part is more trivial than one might imagine; deepest fears or repressed goals, problems experienced in life, aren't turning up so much. Some, sure, but it seems to include more noise. Ego seems to drive a lot of it; random self-association, something like short-term goals or reactions. Once in awhile an interesting idea gets mixed in.

It seems necessary to move past a constant daydream phase, the second part you experience, to get to deeper insights. Noticing thought patterns and letting them go leads to this gradual calming. There is a very pleasant, deeper calm that can occur, which you can't necessarily trigger intentionally; it's interesting when that happens.

This still lacks a lot of guidance about sitting on a mat or not, closing your eyes or looking at the wall, or even returning focus to breathing instead of thoughts (it's simple, but it might not seem so easy or natural in practice). It's probably as well to leave all that vague. It goes without saying that using a timer makes a lot of sense, otherwise you'd never stop thinking about how long it had been, or would look at a clock the whole time.

Between those parts about mental experiences, and another main outcome being body tension reducing and moving around it, it doesn't sound like time well spent, does it? Maybe not. Maybe I should free up 10 days and get some input on a retreat, although that's not something that could align with my life, for the next decade or so.

I would never choose to spend 10 days on a retreat versus with my kids, unless I could expect far more dramatic positive results than I've ever had reason to expect. It's my job as a parent to never make a choice like that, as I see it. I'm separated from my kids for 4 months now, as things stand, but I'm also working to earn a living to support them, so dropping out for a long week would relate to missing a long week of time with them later. It's a no-go.

That's pretty much it for background context too, as far as I need to go. I live in Bangkok, working, although I will return to working remotely in January--I think--while living in Honolulu with them, where they are now. The rest is complicated but not so relevant. There was another story about problems related to a cat but I'll leave that out too (it is covered in a post here anyway). I'm living with three cats now, and it's nice how they practice meditation along with me, only fighting each other, knocking things over, or asking for attention once in awhile. They get it; they want to be supportive.

I would recommend trying out limited meditation, and then if it seems interesting or productive maybe looking into getting better guidance in a meditation center somewhere. I'd recommend trying out fasting too, but running probably isn't for everyone, since there are less impactful ways to become more active and then get fit.

If you have good faith in your joints then why not though; get on with running. Walking quite a bit can help as an early transition, then running mixed with jogging while your body adjusts more, trying to ramp up distance and pace very, very slowly only later on so that you don't get hurt. Wearing good shoes should help, and talking to a doctor if any part seems questionable. Of course I wonder if I won't pay a price, having knee problems later on. Never mind later on; it's been a rough month for one knee.

As for meditation I don't see much related to it being scary, dangerous, or even potentially negative. Just as someone with a heart condition could drop dead if they try to run someone with a severe underlying mental condition might experience some serious problems. You could get a doctor to check your cardiovascular health easier than mental health could be reviewed, but I think most people would be fine meditating, with limited trial exposure. As with running practicing moderation in increasing duration would seem to make sense; there is no need to go straight to longer sessions.

I just saw something about a "quiet walking" trend on Tik-Tok, about a girl filming herself walking without any electronics (or simulating that, since the video recording is surely on a phone?). If someone feels anxiety if they don't use their phone for 10 or 15 minutes I'm not sure how seated meditation would work for them.

Mindfulness practice versus meditation

It's tempting to keep going, to add tangent after tangent. Core Buddhist teachings about the experienced self and nature of reality come into play. That context informs what meditation practice is about, what an expected outcome might be, how ideas and perspective make up an ordinary worldview, which can be adjusted to a more functional version. It's unique how that's generally all a "negative" model, about removing errors included at the level of assumptions, so that you end up with a lighter and lighter final model of reality, that tends to function better and better. Later functional approaches and acceptance tend to replace internal assumed modeling.

It's as well to not go there though; covering this much seems appropriate. Good luck if you plan to try it out. Again I'm no expert or authority on the subject but if you get stuck you can reach out to me to discuss part of it. I'm definitely not into any sort of "life coaching," but you can imagine how embracing Buddhism tends to couple with being open to helping people.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment